For a very long time I have hated sleep. It was rude, inconvenient and most importantly, I didn’t understand its purpose. I always thought to myself “What if there was some secret way that I could always be awake and learning”. In fact, it was the lack of time I had available to learn (mostly due to the fact that I run a business), that I felt frustrated in sleep for getting in my way.

Having some time on my hands over the holidays, I bought a book called “Why We Sleep”, written by neuroscientist Matthew Walker who has been researching sleep for 20 years and published over 100 papers on the topic. It’s the first book of its kind…ever, really. Before this book there were books like “Sleep” by Nick Littlehales and “Sleep Smarter” and “Sleep Better”. But they were all really focussed on techniques for sleeping better, not understanding the why, as well as the consequences of not sleeping. From what I can tell, this is the very first to bring together all the science and answers into one spot.

I devoured this book in 2 days and thought I’d summarise all the most salient bits for anyone who is interested in the science and reason behind why we sleep and why it is so important (especially my little sister who’s sleeping patterns are erratic due to her work).

This new information has immediately changed my behaviour which I will showcase below:

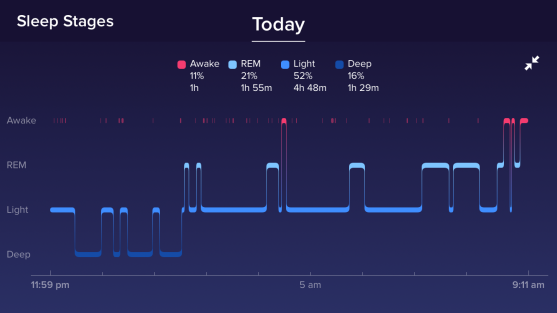

This was how I slept last night…

Fitbit image of my sleep over an 8 hour period. See how the time in REM increases in those final two hours. Had I slept 6 hours, I would not have received any of that REM stage sleep – which we’ll discuss why that is SO important later on in this post.

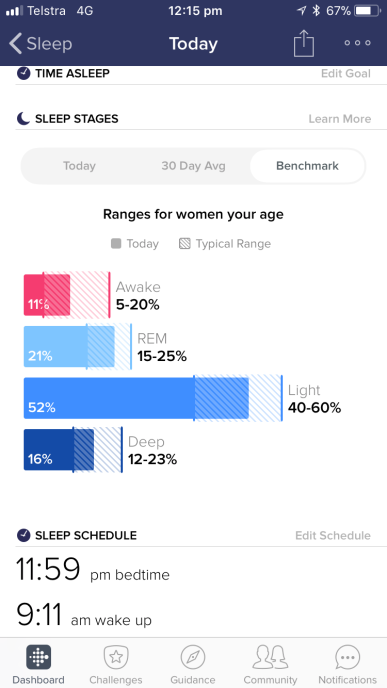

According to my Fitbit, the amount of sleep in each stage was perfect for the benchmark.

Image of my night’s sleep in comparison to benchmarks. Noice.

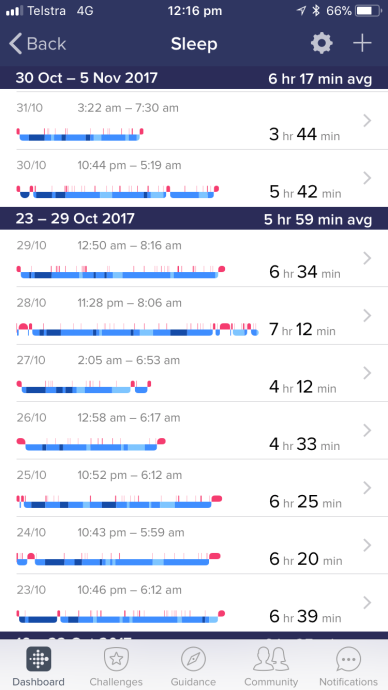

Prior to that however, I had been completely neglecting my REM sleep. This was what my sleep looked like in late Oct, early Nov this year.

Image of my sleep before this book…eeeep!

Matthew Walker hits the nail on the head with this passage from Page 5 of “Why We Sleep”:

Society’s apathy toward sleep has, in part, been caused by the historic failure of science to explain why we need it…To better frame this state of prior scientific ignorance, imagine the birth of your first child. At the hospital, the doctor enters the room after preliminary tests and says “Congratulations, its a healthy baby boy. We’ve completed all of the preliminary tests and everything looks good”. She smiles reassuringly and starts walking toward the door. However, before exiting the room she turns around and says, “There is just one thing. From this moment forth, and for the rest of you child’s entire life, he will repeatedly and routinely lapse into a state of apparent coma. It might even be filled with stunning and bizarre hallucinations. This state will consume one-third of his life and I have absolutely no idea why he’ll do it, or what it is for. Good luck!”

SLEEP RHYTHM

- We all have a biological clock called the suprachiasmatic nucleus

- This clock, which is called our “circadian rhythm”, is approximately one day…but not exactly. Mostly it’s a little more than a day – around 26 hours. (p17)

- What the suprachiasmatic nucleus does is it sits in the middle of your brain just above the crossing point of the optic nerves coming from your eye balls which meet at the middle of your brain and then switch sides. Why? So it can “sample” the light signal being sent from each eye along the optic nerve and use it as reliable light information to reset the inherent time inaccuracy we have. DAMN, What??! (p18)

- Our core body temperature goes up and down in line with this rhythm every day. (p19)

- Whether you are a “morning” or a “night” person (your chronotype), depends on your genes (as discovered by these guys over the course of 20 years of research). This means we cannot control our desire to be an early riser or a late sleeper – but unfortunately work, school and other schedules don’t care about this. (p21)

- Melatonin is a hormone released from the pineal gland in the brain that is kind of like the voice of the timing official in a running race that pulls the start trigger. It gets released every evening, on average it picks up pace after 6pm and reaches its peak at 1am. (p22-24)

- For every day you are in a different timezone (this includes daylight savings), your suprachiasmatic nucleus can only adjust by 1 hour. So if you’re in a timezone 15 hours behind your own, you’ll take about 15 days to fully readjust. Or if going between night and day shifts, that means even just 2 shifts per month will mean your body is in a constant state of playing catch up. (p25)

- Scientists have found the strain of constant jetlag physically shrinks the learning areas of the brain and short term memory is significantly impaired, along with far higher rates of cancer and type 2 diabetes compared to the rest of the population or even carefully controlled match individuals who don’t travel as much (p26)

SLEEP PRESSURE

- The other factor that determines when we wake or sleep is a chemical called adenosine which continues to increase with each moment we’re awake and that increases your desire to sleep. (p27)

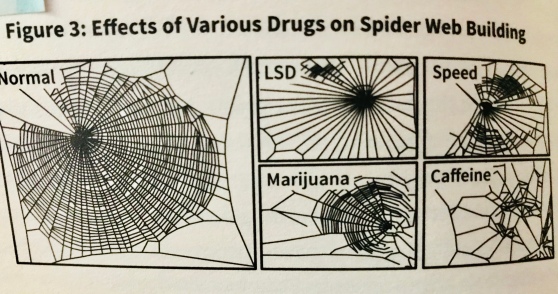

- You can artificially mute this sleep signal with stimulants (the most widely used of which is caffeine but can also include chocolate and types of teas). Stimulants latch on to the adenosine receptors in the brain and stops adenosine from communicating to your brain that you are, in fact, sleepy! With a half life of 5-7 hours to get out of your system, many bad nights of sleep can come from the cup of coffee you had at 6pm. (p30)

Enough said about why caffeine is so bad for you…just because society has completely normalised it doesn’t make it good.

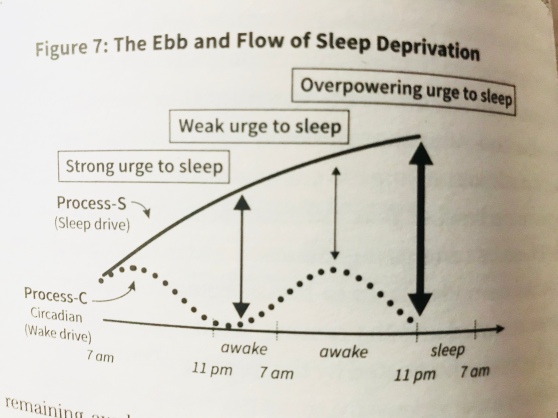

- In theory the longer you’re awake the sleepier you should feel BUT your circadian rhythm and the sleep pressure are two connected processes but not reliant on one another. This is why when you have an all nighter, you may feel very tired around 5-6am but get a 2nd burst of energy in the morning when your underlying circadian rhythm is telling you it’s day time again! (p34)

GENERATING SLEEP

- There are two categories of sleep:

-

- NREM (Non rapid eye movement sleep – broken into x2 stages of light sleep and x2 stages of deep sleep)

- REM (rapid eye movement sleep). This is when you dream.

- The sleep cycle doesn’t repeat itself exactly. During the 2nd half of the night (or the 2nd 4 hours of an 8 hour sleep), you’ll see more REM sleep occuring on each cycle and you get slightly more REM on each cycle. When you cut your sleep short, that’s the bit that you’re most likely to be missing out on. (p42-43)

- If you were to convert the NREM sleep into a sound, you’d hear a quick sound trill every now and then, lasting a few seconds – like a fast purr of a cat. These are called “sleep spindles” and one of their jobs is to protect your sleep by shielding you from external noises. (p49)

- The deepest and slowest brainwaves of NREM sleep are pretty damn amazing – it’s a complete display of neural collaboration. When you’re awake, your brain is like an FM radio station – everything in its spot, communicating in its own section of your brain, but it can’t communicate past that point. When you enter this stage of sleep your brain starts to “sing” together and those waves lengthen out like an AM radio station. They do this so they can communicate their data across longer distances, to process your short term memory across to your long term memory. Like a data back up of sorts! (p50 and 51)

- Waking brain activity is mostly concerned with data reception, while NREM is a state of reflection that helps to transfer and distill the memories of the day and REM integrates it all that new info together with all your past experiences to help you build a more accurate model of how the world works (p52 and 53)

- When you are in REM sleep, you are completely paralysed. Have you ever tried to wake yourself out of a bad dream in the midst of screaming and then as you come into wakefulness you think you’re shouting but your mouth is shut and you can’t move, and then you let out a small whimper once you’re able? Then you’ve experienced a slip in the cross over of that state of paralysis. You truly were unable to move… (p54)

- Why did evolution do this? So that we didn’t go crazy and act out our dreams of course! Makes a lot of sense. (p54)

TO DREAM OR NOT TO DREAM

- If your brain is given the option between NREM or REM sleep after being deprived of sleep, it will feast on the NREM sleep first on the recovery night, but then it will switch to more REM on the following nights – so I guess it must be “batch downloading” and then “batch processing” which makes sense. (p63)

IF ONLY HUMANS COULD

- Dolphins dream with half their brain at a time. One half needs to stay awake to maintain life necessary movement in the aquatic environment. (p64)

- Birds can do the same! (p65)

HOW SHOULD WE SLEEP

- Biologically we have a biphasic sleep pattern, that means we are built to have one long sleep, as well as a nap somewhere between 12pm and 3pm in the afternoon. (p69)

- This means all that time I thought I was feeling tired after lunch, the real reason is that my biological clock was TELLING me I am tired…regardless of whether lunch has been eaten or not.

- When Greece changed to remove the afternoon nap that had been the cultural norm, scientists studied the outcome by comparing those who removed the nap to those who did not across 23,000 Greek adults across 6 years. Those who abandoned the nap went on to suffer a 37% increase risk of death from heart disease – especially working men where the risk of non napping increased to over 60%. WHAT?? This is insane. (p71)

WE ARE SPECIAL

- The amount of sleep we humans get in comparison to other primates is quite a lot less – 8 vs 15, BUT we have a disproportionate amount of REM sleep, between 20-25% vs 9%. (p72)

- REM sleep allows us to regulate our emotions. It basically builds our EQ. If you scale this across millennia, you can start to see how this REM sleep pattern contributed to the rich socio-emotional basis of modern society (p75)

- The second thing that REM sleep contributes to is creativity. NREM sleep helps transfer and make safe newly learned information into long-term storage sites of the brain. But it is REM sleep that takes these freshly minted memories and begins colliding them with the entire back catalogue of your life’s autobiography. These mnemonic collisions during REM sleep spark new creative insights as novel links are forged between unrelated pieces of information. Sleep cycle by sleep cycle, REM sleep helps construct vast associative networks of information in the brain. REM sleep can even take a step back and divine overarching insights and gist – that is, what all knowledge gathered means as a whole vs collection of separate pieces of information. (p75)

SLEEP BEFORE AND AFTER BIRTH

- Babies spend most of their time, in utero, inside REM sleep. Babies kicking around in there aren’t in response to their parents playing music or speaking but are more likely random burst of brain activity that are typical of REM sleep (sorry first time Mums!). The difference with babies is at this point the brain hasn’t developed enough to paralyse them while they’re in this sleep state as it would when they come into the real world, so off they go, bopping around like its a dance party in there! (p78)

- Ignoring severe alcoholism during pregnancy, even mothers who might have a quick glass of wine or two have a significant impact on the REM sleep of the fetus. After just a glass or two, the unborn infant’s breathing rate drops from 381 per hour to 4 per hour. Holy crap! Later on the book Matthew Walker refers to research around just human consumption of alcohol and what it does to sleep and the ability to learn…so just imagine what this could be taking from a new human attempting to form its entire physiology? (p84)

- About half of all lactating women in western countries consume alcohol in the months during breastfeeding. But sleep data brings this into question. Newborns normally transition straight into REM sleep after feeding and in several studies where infants have been fed alcohol laced milk, their sleep is more fragmented, they spend more time awake and suffer from a 20-30% suppression of REM sleep. They’ll often try to get it back once it has been cleared from their bloodstream but it’s not easy for their fledgling systems to do so. What’s scary is we really don’t know what the long term effects of REM sleep disruption in babies really is at this point (p84-p85)

CHILDHOOD SLEEP

- The older a child gets, the longer and more stable their sleep becomes. This is because their suprachiasmatic nucleus (their biological time clock) doesn’t finish developing until 3-4 months. Remember how it was noted that the nucleus “samples” light from the optic nerve? Well as many people know, babies eyes haven’t fully developed at birth – I imagine this impacts on the nucleus’ ability to even sample light accurately… (p86)

- At 6 months, there is a 50/50 time share across a 14 hr sleep period between NREM and REM sleep while at 5 years, there is a 70/30 split between the two (p87)

ADOLESCENT SLEEP

- A second round of brain wiring re architecture happens at the start of adolescence. Its goal is efficiency and effectiveness. This stuff completely blew. my. mind. I’m going to just pop in the analogy direct from the book because it explains the process really well:

- “When an internet service provider first sets up a network, each home in the newly built neighbourhood was given an equal amount of connectivity bandwidth and thus potential for use. However, that’s an inefficient solution for the long term, since some of these homes will become heavy bandwidth users over time, while other homes will consume very little. Some homes may even remain vacant and never use any. To reliably estimate what pattern of demand exists, the Internet service provider needs time to gather usage statistics. Only after a period of experience can the provider make an informed decision on how to retune the original network structure it put in place, dialing back connectivity to low-use homes, while increasing connectivity to other homes with high bandwidth demand. It is not a complete redo of the network, and much of the original structure will remain in place. After all, the Internet service provider has done this many times before and they have a reasonable estimate of how to build a first pass of a network. But a use-dependent reshaping and downsizing must still occur if maximum network efficiency is to be achieved.” (p88)

- The change in NREM sleep always precedes the cognitive and developmental milestones within the brain by several weeks or months, implying a direction of influence: i.e. deep sleep may be the driving force of brain maturation, not the other way around. (p90)

- When scientists deprived juvenile rates of deep sleep, they halted the maturational refinement of brain connectivity, demonstrating a causal role for deep NREM sleep in propelling the brain to healthy adulthood. (p91)

- A separate series of studies observed that in young individuals at high risk of developing schizophrenia, there is a two- to threefold reduction in deep NREM sleep. Furthermore, the electrical brainwaves of NREM sleep are not normal in their shape or number. Faulty pruning of brain connections is now one of the most active areas of investigation in psychiatric illness. (p92)

- Adolescent teenagers have a different cercadian rhythm to both their parents and their young siblings. A 9 yo rhythm would sleep at 9pm, while a 16 yo would still be at peak wakefulness perhaps even to 11am or 12pm. Asking a teenager to go to bed at 10pm is the circadian equivalent of asking a parent to fall asleep at 7pm. (p93)

SLEEP IN MID LIFE AND OLD AGE

- Broadly speaking, older people need just as much sleep as we do – however their machinery for creating powerful sleep pressure and circadian rhythm change in such a way that it makes it more difficult to get the sleep they need. i.e. it is a myth that “older people need less sleep”. (p95-99)

- Matthew suggests two modifications for seniors lifestyles who are exercising to help sleep onset – when exercising in the morning, wear sunglasses to reduce the effect of sunlight on your suprachiasmatic clock that would otherwise keep you on an early-to-rise schedule. Plus, go back outside in the late afternoon for sunlight exposure but this time don’t wear sunglasses, this will help delay the evening release of melatonin and push the timing of sleep to a later hour. (p100)

In Part 2 of this post I’ll cover off why you should sleep – backed by a bunch of scientific data referenced in the book.

Excellent post, as I’m in the throes of a disturbed pattern. Typically, I could summon sleep just by being still for a second or two.

Regards, pierre.

On 3 January 2018 at 12:34, Learning without University wrote:

> michellebourke posted: “For a very long time I have hated sleep. It was > rude, inconvenient and most importantly, I didn’t understand its purpose. > I always thought to myself “What if there was some secret way that I could > always be awake and learning”. In fact, it was the lack ” >

LikeLike

Hey Pierre! I’m sorry to hear you’ve got a disturbed pattern at the moment. Part two of this post which I’ll do in the next week or so will also cover more of the ‘why’ and some scientifically tested ways of increasing ability to sleep. New microbes (if you changed diet recently), caffeine (not just in chocolate but in tea, chai lattes and more), any kind of alcohol at all – even a glass or two, watching screens (or reading on a screen) 2 or less hours before bed, drinking too much water before bed, not exercising regularly, stress at work but no meditation or similar to help disconnect from it and being a new parent. Those are all the things I can think of that disturb sleep significantly. Have you experienced a change that might align with your sleep disturbance with any of the above?

LikeLike

A very well summarized and scientific post. Loved to understand the science behind Sleep for every stage of life. I usually felt, 8 hrs recommended sleep was more for me. Everyone around me scared me saying, you will develop ‘n’ number of problems sleeping for 5 hrs……Bought a fitbit to observe my sleep pattern and sometimes forced myself to sleep over weekends to practice sleeping…he he….Your post has removed my doubts of having an unhealthy life if a person has a sound 5-6 hrs sleep.

LikeLike

Hi Sheetal! Yes I was definitely surprised to learn that the reality is as scary as your friends probably made it out to be – maybe even more so.

Does your Fitbit give you your sleep stages as well? I know my old one didn’t seem to so I only have cycle sleep data going back to about November 17.

One thing I’ll cover in the next most on why we should sleep is that also what I used to do is sleep less during the week and have a big sleep in on the weekend. Apparently you can never ‘make up’ the sleep deficit. Your body does try to – but it cannot ever get back what it lost. 😞

LikeLike

Hi Michelle ! My Fitbit does not give the stages as shown in your post. It shows in a different format. It just has Awake, Restless and Sleep.

https://www.screencast.com/t/AvHmWNCFU4

Looking forward to your next post 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah yes I think my old one had that too – Simon bought me a new one as a present and I noticed it after that so it must be the version of Fitbit you have. Also I just posted the next post today – still have a few more posts on this topic to go 😀😎

LikeLike