Last week CNN posted an article with the title “Drinking non-cow milk linked to shorter kids, study suggests“.

Let me start by saying, that this statement is in fact correct…but not for all intents and purposes. What does that mean? Let’s start at the beginning.

In the media model, article views equals the ability to sell more advertising space which equals revenue for shareholders. In the science model, replication of a well designed study by other well designed studies and producing the same result (a process that can take years, sometimes decades!) equals an answer that may then be worthy of writing an article about. These organisational models are living in parallel universes where time between them runs at different speeds. And this is a shame for the consumer.

Imagine a world where as a consumer, you had access to an instant meter of how valid the results of any research study was according to some universally accepted scoring criteria so you weren’t at risk of consuming erm…trash.

Before you read another click-baiting, crowd-pleasing, over-shared, under-researched article, I’m going to jot down a few things for you to take note of, or to take a few extra minutes to research after you read any article reporting on a new scientific finding. I challenge you NOT to either share the research nor commit the findings to memory until you’ve availed yourself of the facts surrounding the research design.

The most important question to ask is: Did the research study control for confounding variables?

A confounding variable happens when a researcher can’t tell the difference between the effects of different factors on a variable. There are so many different things that can have an impact on the results of the study and so understanding what “data noise” to remove is critical to making sure that pattern in the data that a researcher might see is unlikely to be due to chance alone.

When reviewing the validity of research results, these are some of the red flags when it comes to research design:

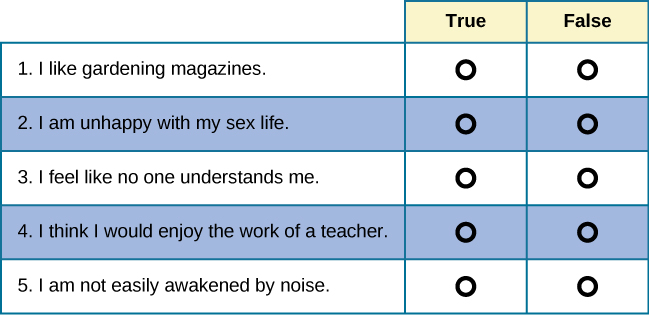

- Self reported behaviour surveys

Humans can barely remember what they did on the weekend let alone on a daily or weekly basis five years ago! That’s not to say that these studies aren’t relevant, simply that the evidence from them would not be considered as strong as say a study where the experimental design had people follow a pattern of behaviour (for the control and placebo groups) across a specific period of time and followed up with them regularly for self reporting across that time period.

- The lack of a control group, test group (and in some cases) a placebo group

A control group is a group of participants to whom the treatment isn’t applied, in the test group the variable that the researcher wants to test is introduced and in the placebo group, the participants think they are part of the test group, but they are receiving some sort of alternative to the treatment that will not yield the expected result. The human brain and body are pretty powerful…when we think we’re getting we can actually experience improvements that don’t really exist!However, a placebo group is not always feasible depending on what is being tested so a bit of common sense needs to be applied here. For instance, if you were trying to test some sort of effect related to drinking water, you could have a control group who didn’t drink water, but given everyone knows what water tastes like, attempting to create a “water placebo” would be pretty tough. But a control and test group should be the bare minimum! And in cases of medication where a placebo can be easily applied, there should ALWAYS be a placebo group.

- Non randomised

If the research is experimental in nature (and not survey based), and the report doesn’t say it’s randomised, then it probably isn’t. A randomised experiment means that participants in the experiment (those put into either control, test or placebo groups) were randomly assigned assigned to them. i.e. that the researchers weren’t in control of choosing who would be assigned to which group. If they are, they can introduce all sorts of unconscious bias that could affect the results.

- Non Blinded or Non Double Blinded

A blinded study is where the participant in the research is unaware which group (i.e. test, control or placebo) they have been assigned to. A double blind study is where neither the participant in the research, nor the researcher themselves, knows which group the participants have been assigned to. That means the researcher might only see a number in place of an individual’s name and details when seeing the results. And the experiment may be designed in such a way that those responsible for data collection, and perhaps physically collecting data from the participants, do not communicate with the researcher (or may not even be known to them).

- Small sample sizes

A “sample” is basically a little portion of the broader “population”. A population in research doesn’t have to mean the population of a country, it may just be the population within a particular category pertinent to the research. For example “people with Diabetes”, or “people who have been treated for depression”, or “women who have given birth to at least one child”. The sample size has, because there are random effects that can occur in small samples that even themselves out when you test the same thing on a larger sample size.Most good research might start with a smaller sample size to test an initial hypothesis (theory). They’ll release initial results but caution that due to small sample sizes, more research should be done to see if the results can be replicated on a broader scale so that it can be . If this is the first research in a particular area to come out and it’s got a small sample size you MUST treat it with caution. It means that it is essentially “baby research” it’s not fully formed yet nor capable of making truly informed conclusions about its own existence!

- Non peer reviewed – i.e published in a dodgy journal

Yep, not all journals are created equal. A good piece of research should be published by a journal that has a process whereby other scientific peers review the research methodology before accepting it for publishing. Sometimes good journals will create a single-blind process for doing this – meaning that those reviewing the research don’t know who the author is. That’s important – because humans have an innate bias to trust people who are perceived to be more credible, despite there potentially being a lack of evidence to support that trust.

If it has been archived or cited here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov that’s a good start. Apparently this tool https://harzing.com/resources/publish-or-perish helps you figure out how many times the article has been cited in journals (although I’ve not used it before) and this one helps you figure out the ranking of the journal: http://www.scimagojr.com/journalrank.php?area=2700&type=j.

Monash Uni have a bunch of good links and info about assessing journal quality here including:

- List of predatory publishing journals (those that don’t apply ethical rigour to the type of research they accept and publish)

- 8 Way to identify questionable open access journals

- Statistical significance without IMPORTANCE

Statistical significance is generally agreed that there is either a 5% or lower (sometimes 1% for more rigorous research) probability that the results obtained were due to chance versus the variable being tested.That’s a great first step for sure, but significance does not mean importance. Once the study has met the above criteria, ask yourself one, final and very important question “Is this question the right question to be asking, and is the assumption that underpins the question being asked a correct assumption?”

Pingback: To drink cows milk or not to drink cows milk – that is the question | Learning without University